How and Why to Develop an Incident Response Plan (IRP)

Why It’s Necessary

The difference between chaos and control often comes down to preparation. An Incident Response Plan (IRP) is a documented set of steps, roles, and processes that guides your organisation when responding to security incidents, helping you reduce the level of chaos during crises. Your IRP is your playbook when a breach occurs; it outlines who does what, how incidents are escalated, and how communication flows internally and externally.

Without an IRP, teams often waste time debating decisions, overlook regulatory obligations, or duplicate effort. In a crisis, every minute counts.

Organisations without an IRP face predictable challenges:

- Confusion over responsibilities: who decides whether (and when) to notify regulators? Who owns customer communication?

- Delayed escalation: frontline staff might sit on an issue too long, unsure when to raise the alarm

- Duplicated or conflicting actions: two teams might attempt different fixes, causing further disruption

- Inconsistent communication: executives, regulators, customers, and the media may all receive different messages

- Unclear expectations: will you (or can you) pay a ransom demand?

- Compromised communication channels: if there’s an adversary in your environment, are they monitoring your IR teams’ communication channels because they’ve compromised O365?

Consider a financial services firm that suffered a cloud misconfiguration. A storage bucket containing customer records was left exposed, and personal data was downloaded by an external party.

Because there was no IRP:

- The IT team spent days debating whether the exposure counted as a “breach”

- Legal wasn’t informed until a regulator contacted the firm directly

- Customer notifications were delayed and inconsistent; some clients heard about it through the media before hearing from the company

- Multiple internal teams duplicated efforts, and critical evidence was accidentally overwritten

The result: reputational damage, regulatory fines, and a loss of customer trust that could have been mitigated with a clear, tested IRP. In most cases, how you communicate what you did is just as important as how you responded.

How to Build an IRP

Building an IRP doesn’t need to be overwhelming. Start simple, make it relevant to your organisation, and refine over time.

Step 1: Define Scope and Objectives

Decide what types of incidents the plan covers: insider threats, accidental data loss, cloud service misuse, misconfigurations. Align these with your business priorities and regulatory requirements. Determine which sites, users, and devices the plan relates to; all of them, or just a subset. For example, if you have traditional IT networks and operational, OT networks, you should have separate IRPs that account for the differences in technologies, architectures, and consequences within those disparate environments.

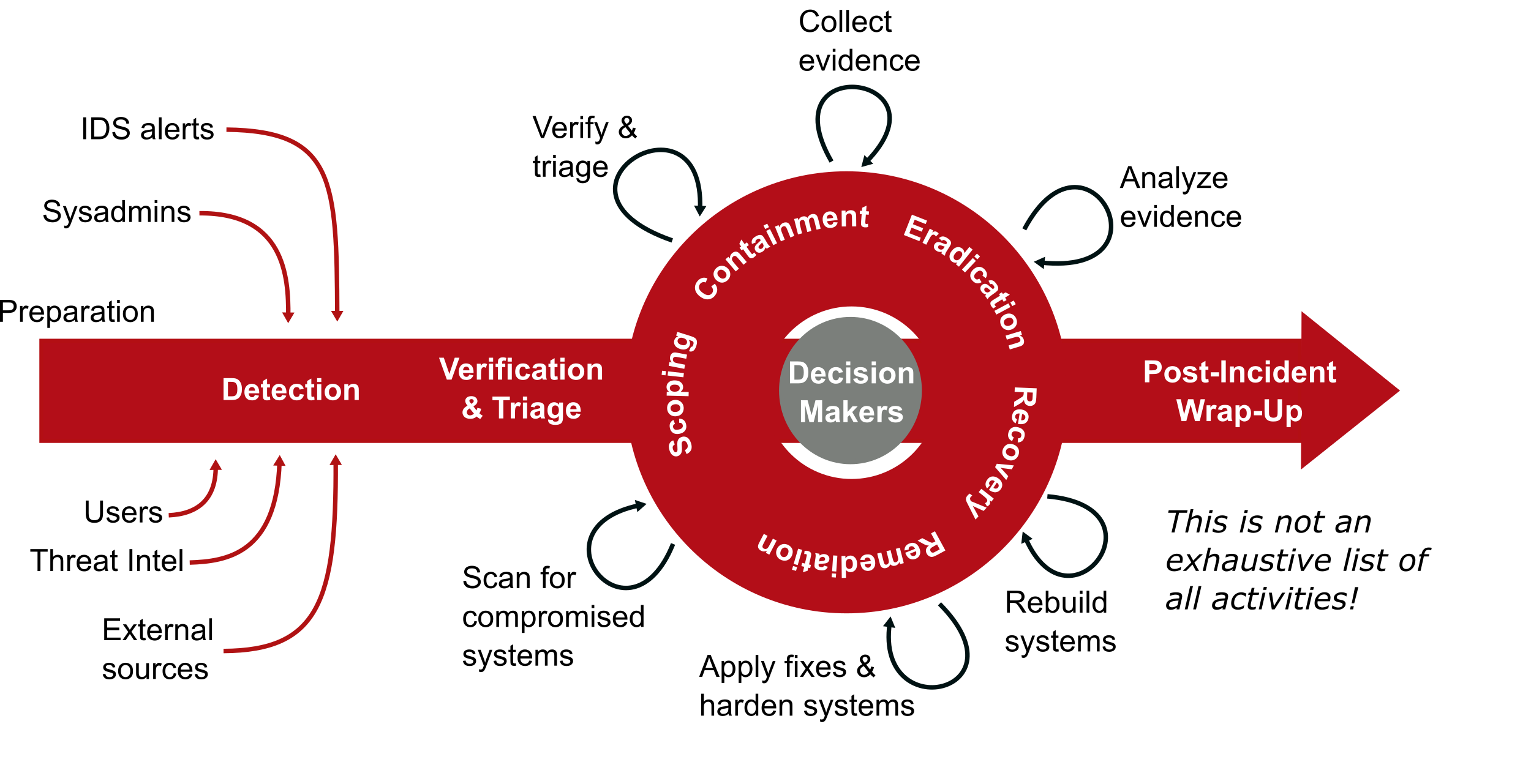

Step 2: Choose an IR Framework

Your IRP should be built on a recognised framework so your team isn’t reinventing the wheel. Frameworks provide structure, a shared vocabulary, and a proven process for responding to incidents. Several well-established approaches exist, each with strengths and limitations. The key is to pick one as your baseline and adapt it to your organisation’s size, culture, and regulatory environment.

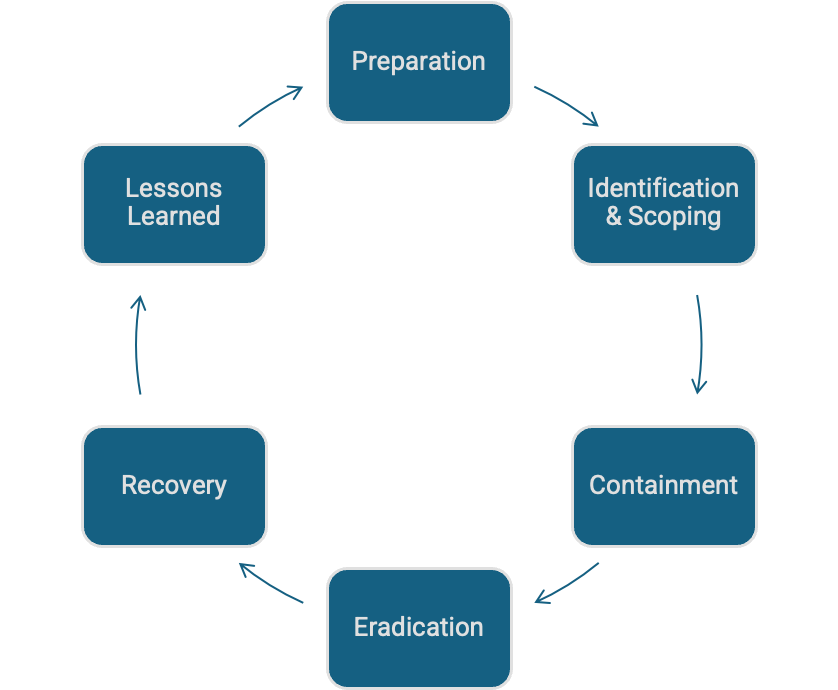

SANS PICERL Model

Pros:

- Widely used globally; plenty of public examples and guidance

- Lifecycle covers both immediate response and post-incident improvement

- Flexible for both technical and management audiences

- Allows communicating across and moving between IR phases smoothly

Cons:

- Can feel linear, even though incidents are rarely neat

- Guidance is US-centric; some terminology doesn’t always fit APAC contexts

- Less explicit guidance on governance, communications, and external coordination

Best fit: Organisations that want a mature, process-driven model with global recognition

Reference: https://www.giac.org/paper/gcih/1902/incident-handling-process-small-medium-businesses/111641

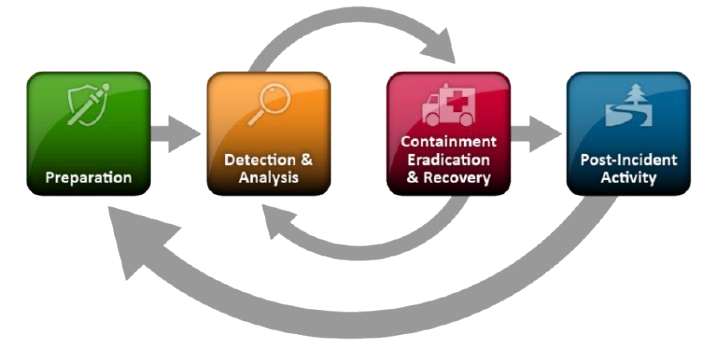

NIST SP 800-61

Pros:

- Detailed guidance, with strong emphasis on preparation and analysis

- Aligns with other NIST frameworks (e.g., CSF), making it easier to integrate with broader risk management and compliance programs

- Offers explicit considerations for evidence handling, forensics, and communications

Cons:

- More complex, may feel “heavy” for smaller teams without mature processes

- Documentation can be prescriptive if adopted without tailoring

Best fit: Organisations with regulatory obligations, or those wanting depth and alignment with NIST CSF and ISO standards

Reference: https://www.nist.gov/privacy-framework/nist-sp-800-61

DAIR (Detect, Analyse, Identify, Recover)

Pros:

- Straightforward and easy for non-technical stakeholders to understand

- Keeps the focus on the essentials: spotting, analysing, classifying, and fixing

- Simpler and faster-moving than PICERL or 800-61; useful for smaller or less mature teams

- Fits well with cloud-first or agile organisations that need lightweight structures

Cons:

- Less detailed than PICERL: limited guidance on containment and eradication

- Can be too simple for complex environments

- Less recognised globally compared to SANS / NIST 800-61

Best fit: Mid-sized organisations without a mature SOC, or as an entry point before scaling into PICERL / CSF

Reference: https://www.cyberengage.org/post/rethinking-incident-response-from-picerl-to-dair

IR Framework Comparison

| Framework | Lifecycle / Phase | Pros | Cons | Best Fit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

MITRE ATT&CK & NIST CSF (as augmentation)

MITRE ATT&CK: A knowledge base of adversary tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs)

How it fits:

- Complements whichever lifecycle you choose by linking real-world attacker behaviours to detection and response steps

- Helps teams map “what attackers do” to “what we need to monitor or collect”

NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF): Provides broader organisational functions (Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond, Recover)

How it fits:

- An IRP supports the Respond and Recover elements and can be cross-referenced to demonstrate governance maturity

When choosing, the best approach is often hybrid: use SANS PICERL as the backbone for training and communication, adopt NIST 800-61 for detailed processes and compliance alignment, and overlay ATT&CK and CSF as tools to enrich detection and governance.

Step 3: Assign Roles and Responsibilities

Use a RACI model (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed) to clearly define who makes decisions, who executes actions, and who needs to be kept informed.

| Role | Responsible | Accountable | Consulted | Informed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Incident Commander | ✅ | ✅ | – | – |

IT Security Lead | ✅ | – | – | – |

Legal Counsel | – | – | ✅ | – |

Communications / PR | – | – | ✅ | ✅ |

Executive Sponsor (CISO / CEO) | – | ✅ | – | ✅ |

Step 4: Document Escalation Paths

Outline how incidents move from Detection to Containment, Containment to Eradication, and ultimately to Recovery and Lessons Learned. Clear escalation ensures no step is missed and that the right people are engaged at the right time. Include contacts for:

- Internal IT / security staff: front-line responders and escalation points

- Managed service providers (MSPs): include service-level agreement (SLA) details and clarify who calls whom, when, and for what type of support

- Regulators: note timelines for mandatory notifications (these differ across jurisdictions)

- Cyber insurers: know how and when to trigger your policy requirements

- PR and legal advisors: pre-identified partners can reduce delays and help control reputational damage

This avoids confusion about who to call, when to call them, and what information they need to act.

Step 5: Outline Communication Protocols

Communication failures often make incidents worse. Document your internal communication policies and who informs executives, staff, and the board. Ensure you’re aware which laws apply and how quickly you must notify regulators of a breach. Before an incident occurs, develop template language for data breach notifications, then determine and record who’s authorised to speak publicly, whether to customers, the media, or other, and what the approval chain looks like.

Step 6: Create an Incident Classification Scheme

Not every event requires full activation of your IRP. Classifying incidents by severity helps your teams calibrate their response without overreacting. At it’s most fundamental, a severity classification scheme might include just three levels:

- Low: Contained quickly, no business impact

- Medium: Limited disruption or data exposure, requires management oversight

- High: Significant business impact, regulatory reporting required, potential reputational harm

Your severity levels will likely develop over time, and will grow to include considerations such as number of endpoints or devices involved, users or customers impacted, and sites affected.

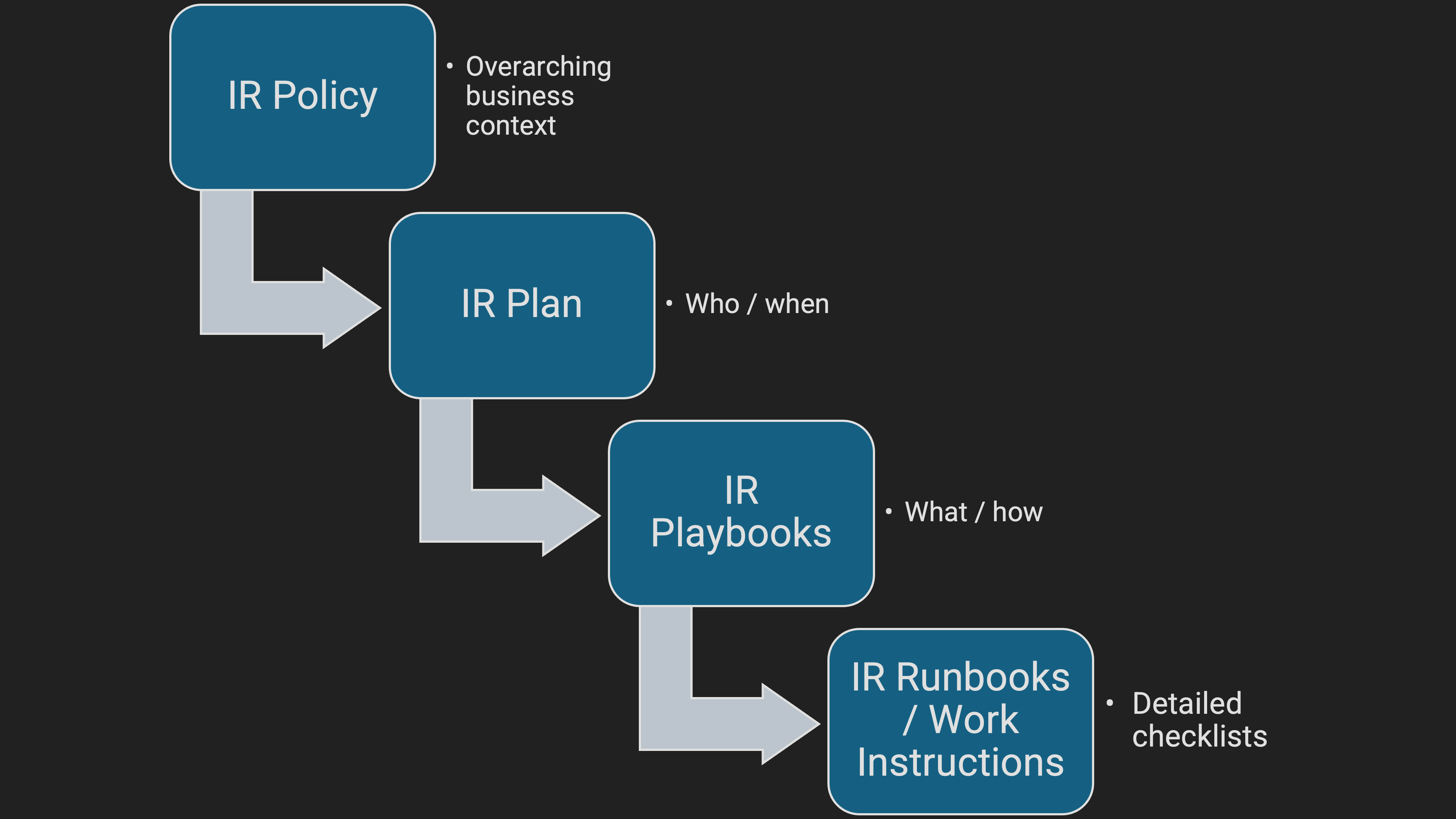

Step 7: Integrate with Existing Documentation

Your IRP shouldn’t exist in isolation. Link it with other documents you likely already have (or consider creating these next), ensuring consistency across all resilience and governance documents:

- Business Continuity Plans (BCP)

- Disaster Recovery Plans (DRP)

- Compliance obligations (privacy, critical infrastructure, sector-specific)

- Backup and recovery plan

Step 8: Test the Plan

An untested IRP is just paper. Run TTXs where teams walk through simulated incidents. Validate escalation paths, test communication templates, and identify gaps. Adjust the plan based on lessons learned.

Best Practices

To make your IRP effective and usable, keep it practical and concise. Avoid 100-page binders that no one reads. Aim for clarity and brevity. Your plan should use plain English so it can be understood by executives and frontline staff alike. Establish a revision cadence, at least annually. Additionally, update your plan after major incidents, organisational changes, or regulatory updates. Align with frameworks but customise. Use NIST, SANS, and ATT&CK as guides, but tailor to your business context. Finally, store it where it’s accessible. Maintain both online and offline copies. Don’t assume your network will be available in a crisis.

An Incident Response Plan is one of the lowest-cost, highest-value maturity steps an organisation can take. It transforms IR from improvisation to coordination, reducing mistakes, regulatory risk, and reputational harm.

If you don’t have an IRP yet, start small: define roles, escalation paths, and communication flows. From there, refine with TTXs to validate assumptions.

In future blogs, we’ll explore how to build incident response playbooks, detailed guides for specific scenarios like phishing, insider threats, and cloud breaches that plug into your IRP and give analysts even more confidence when it matters most.

Disclaimer: This content may have been edited or refined with assistance from AI tools. All final content, views, and recommendations are our own.